About

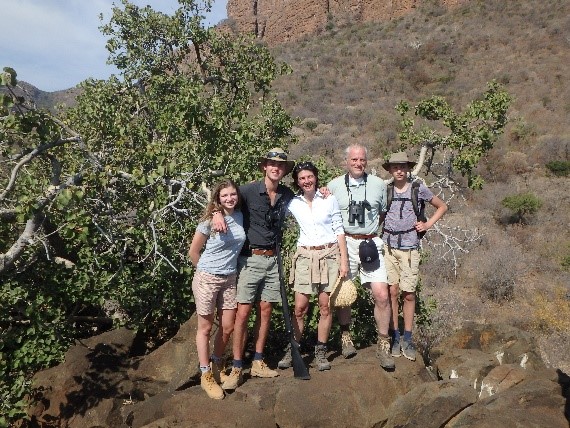

Harriet Stoop (1964) is a passionate artist and makes sculptures of mammals and birds in bronze and ceramics. A characteristic of Harriets’ sculptures is the subtle way in which she depicts the activity of her objects. Every living creature in the wild is alert and interacts with its environment. Harriet observed the movement and behaviours of mammals, birds, reptiles and insects in Kenya, where her parents used to live, and also during safaris in South Africa and Botswana.

Each of Harriets’ sculptures refer to a magical moment, an encounter with a mammal or a bird. To create a sculpture, memory is not enough. Harriet investigates the construction of the skeleton and muscles of the creature and its movements. Photos, videos and sketches lead to a three-dimensional composition in clay. This model, together with anatomical drawings, form the base of the armature, a wire frame. And then the modelling in wax begins! Layer upon layer.

Every sculpture has a story. The Secretary Bird is an ode to her father, Titus de Meester (1927-2015). Titus was a keen ornithologist and the secretary bird was his favorite bird. His decision to work and live with her mother in Kenya resulted in Harriet falling in love with the African wilderness.

The figures of the African wild dogs were made after Harriet first saw a pack of wild dogs hunting. With a barking sound wild dogs communicate with each other over long distances about bringing down their prey. Fascinating is seeing one wild dog staying behind and giving instructions.

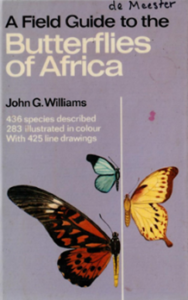

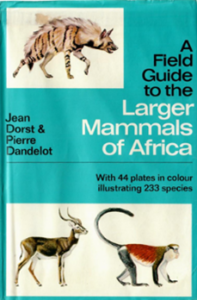

If you notice the tracks of the pangolin, with the prints of its hind legs and the mark left by its trailing tail, you wonder what this mammal looks like. It is very rare to find a pangolin because there are not many left and they are extremely shy.

When Harriet started modelling this amazing anteater she came across a very special book: Photographers against WILDLIFE CRIME, with a rolled up pangolin on the cover, and a shocking documentary about Maria Diekmann: Pangolins, unknown but highly sought after. Maria takes exhausted pangolins from under poachers’ beds and gives them a new life. Incredible! Harriet decided to send part of the proceeds to Maria’s shelter in Namibia (https://www.pangolins.international/). The survival of the pangolin is in danger! An extra reason to make a sculpture of this beautiful mammal was to increase awareness.

The inspiration for the sculpture of Lilly and Henk are the videos of the baby rhino playing with the goat, taken by Harriets’ son Dirk. Lilly was a 6 month old orphan. Her mum has been poached. The goat Henk teaches Lilly to graze and also became her playmate. Lilly had to be guarded day and night, because the poachers are never far away! One of the guards was Dirk.

Part of the proceeds from this bronze of Lilly and Henk, goes to Cycling4Wildlife, an initiative of 4 boys (Huib, Thomas, Willem and son Jan) to cycle 5000 km. through Africa to raise awareness of the vulnerability of the African wilderness and to raise money for an environmental education program for local communities organised by African Parks.

Two worlds come together in Harriets’ process of making sculptures: as an art historian (UVA 2004) she developed an eye for detail and as a fashion designer (Charles Montagne 1986) she got the experience of giving shape to an idea or a design in three dimensions, not in wax or clay but in silk. “When making sculptures you have to think three-dimensionally, which I find very exciting. It is literally adding an extra dimension when compared to making a drawing or a painting working on a flat surface. This extra dimension is about volume and direction.”

Because of her art historian research, Harriets’became an expert on the 17th-century Dutch painter Gerrit Lundens (1622-1686). A beautiful painting The Fair Guests, painted by him used to hang in Harriets’ grandmother’s house, is the first work of art that made a huge impression on her as a little girl. She could look at it endlessly.

Her interest in this painting encouraged her to study History of Art at the University of Amsterdam (2002), after working in fashion for 10 years. While looking for a thesis-topic, she approached professor Ernst van de Wetering, in the institute of History of Art in Amsterdam. When she showed him a picture of this painting, he couldn’t believe his eyes: ‘It is the composition of The Night Watch! A trouvé!’ A reduced copy of The Night Watch was attributed to Lundens and this painting of her grandmother later turned out to be the conclusive piece of evidence that Lundens was the painter. Extensive research followed. Harriet graduated and eventually a publication from her hand was published in the Rijksmuseum Bulletin (vol 68, 2020/2). Further, in an article in the NRC (24 Sept. 2021), she argued for a full reconstruction of the original composition of The Night Watch. She continues doing research on Lundens’ oeuvre.

As a freelance curator, she puts together exhibitions and gives talks about contemporary artists. To showcase the quality and diversity of contemporary Dutch portrait art, Harriet has written two books together with co-author Cathinka Huizing (1961-2020): Portraits of Portraitists (Waanders 2010) about contemporary portrait painters, and Dutch Identity, Portrait Photography Now (Waanders & De Kunst 2016) showing the depth of Dutch contemporary portrait photographers. Both books were accompanied by an exhibition in the Museum De Fundatie in Zwolle. “Working together with Cathinka, was great fun, we were a perfect team. On top, I learnt a lot from all the artists we have interviewed.”